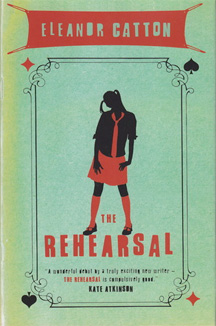

Eleanor Catton’s The Rehearsal (2008)

Eleanor Catton’s The Rehearsal (2008)McClelland & Stewart, 2010

I felt like a teenager when I started reading this novel. I’d switched purses seasonally and forgot to transfer my housekeys, so I ended up sitting on the front porch for a few hours waiting for Mr. BIP to come home.

I forgot my keys a lot when I was a kid, so if I hadn’t already been a reader, I probably would have become one from the need to fill time whilst waiting for someone to come home and let me in.

I often stopped at the school library or the local library on my way home from high school, and I always had reading material at hand, and I had luckily stopped at the public library that afternoon for The Rehearsal, so my porch-sit was actually quite enjoyable.

(Actually, it was all the more so because I couldn’t possibly feel guilty for reading because I really had no other choice, not being able to get in to do the myriad of chores that I’d actually planned to do when I got home). It was a beautiful near-summer day and I pulled a bag of pistachios from my purse and nestled into the cushioned chair to read more than 250 pages — before heading down the block for an iced americano and the use of a pay phone.

It was a comfortable set-up, but not a comfortable read: Eleanor Catton’s The Rehearsal captures adolescence and coming-of-age-ness with an unflinching honesty. The complexity of her characterization is almost overwhelming at times and, appropriate to her characters’ world-revolves-around-me lifestage, everyday events and exchanges are observed and analyzed with a peculiar intensity.

“It is a mark of the depth of their wounding that they are pretending they suspected it all along. Everything that they have seen and been told about love so far has been an inside perspective, and they are not prepared for the crashing weight of this exclusion. It dawns on them now how much they never saw and how little they were wanted, and with this dawning comes a painful reimagining of the self as peripheral, uninvited and utterly minor.” (59)

It’s spot-on, isn’t it. Belonging and alienation, identity and searching, importance and insignificance: these are contrary times. The varying perspectives, the constant shifts in focus that underscore the larger question of what is real and what is portrayed, what exists and what is performed: it’s disorienting.

But “…you must start with a thing itself, not with an idea of a thing. I can see what I am holding in my hand. I can see its weight, its shape and its texture. It doesn’t matter if you can see it yet or not: the important thing is that I can.”

The Head of Movement at the drama school explains this, but I’m pulling it out to demonstrate that the same is true of Eleanor Catton: it doesn’t matter if you can see it or not, she is up to something, right from the start.

The novel begins with alternating segments told from the perspective of schoolgirls (including Isolde, whose sister Victoria has been implicated in a scandal/crime/pantomime involving the jazz band teacher Mr. Saladin) and their saxophone teacher; the second chapter adds drama classes to the first’s music classes, fleshing out ::cough:: another layer to the performance theme. And this? This is the straightforward part.

If you enjoy literary fiction not just for a good story, but because you like to marvel at the way in which a good story can be constructed?

If you read literary fiction not just because it raises questions and gets your readerly-ness spinning, but because the degree of spin is sometimes so disturbing that you lose your reader’s centre and are forced to reset your own understanding of narrative truth?

If you like the idea of spending more time talking about a book than you’ve actually spent reading it, even though you might end up less sure about some aspects of it when you’re done talking than you did before you started?

Then I think you would enjoy The Rehearsal. (I do enjoy a good puzzle myself, and the layers in Catton’s novel are fascinating, but it was my interest in coming-of-age novels — and the number of years I spent in music classes as a kid — that sealed the bookish deal.)

Why else might you want to read Eleanor Catton’s debut novel? Well, as Stanley says “Because if somebody’s watching, you know you’re worth something.” And there are a lot of people watching Eleanor Catton. The reasons for that are twofold, I’d say. [Note: Rehearsal inside-joke.]

PS This was originally posted at BuriedInPrint and I just realized that I should have been cross-posting those reviews here too.

No comments:

Post a Comment